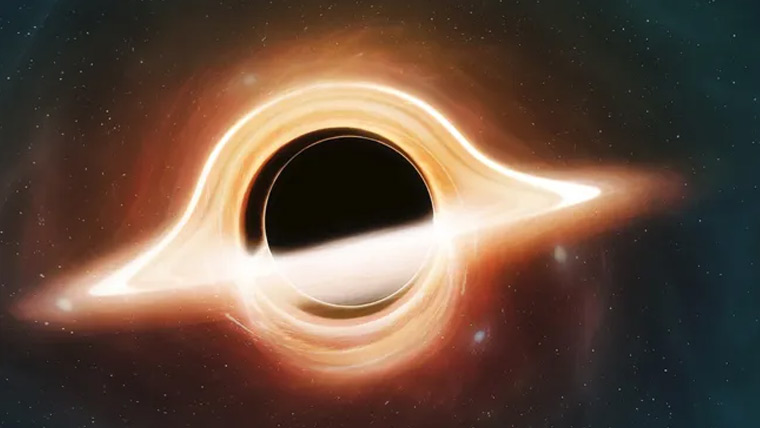

London (Web Desk): In a landmark discovery for astrophysics, scientists have documented an extraordinarily powerful burst of light emanating from a supermassive black hole—an event now officially classified as the brightest ever detected in cosmic history. This colossal emission, known as a tidal disruption event (TDE), was generated when a colossal star strayed too near the black hole and was consequently shredded by its overwhelming gravitational force. The observation provides invaluable insights into the extreme physics governing the universe’s most enigmatic objects and the dynamics of early galactic nuclei.

The Record-Shattering Light Emission

According to comprehensive reports, including those from Reuters, experts have determined that at its apex of intensity, the observed flare was an astonishing 100 trillion times brighter than our Sun. The magnitude of this luminosity far surpasses any previously recorded stellar-disruption event, offering astronomers a unique opportunity to study the processes of accretion and energy release under conditions of immense gravity.

The cosmic event originated from a black hole situated at the core of a distant galaxy, located approximately 11 billion light-years away from Earth. This immense distance means that astronomers are effectively looking back in time by 11 billion years, observing a phenomenon that occurred during the universe’s early stages. This temporal window allows researchers to examine the physical characteristics and behaviours of supermassive black holes when the universe was significantly younger.

Black holes are recognised as regions of spacetime exhibiting such powerful gravitational effects that nothing—not even light—can escape from within a certain boundary. Current astrophysical theory posits that virtually every large galaxy, including our own Milky Way, harbours a supermassive black hole at its galactic centre. The black hole responsible for this record-breaking flare is estimated to be approximately 300 million times heavier than the Sun. This measurement indicates that it is vastly larger and more massive than the Milky Way’s central black hole, Sagittarius A*, which weighs approximately four million solar masses.

The Mechanism of Stellar Destruction: Spaghettification

Scientists propose that the colossal burst of light was triggered when an exceptionally massive star was gravitationally drawn into the immediate vicinity of the black hole. As the star’s material was pulled beyond the event horizon—the point of no return—an immense release of gravitational potential energy was converted into luminous energy. The doomed star itself was formidable, estimated to have been at least 30 times the mass of the Sun, with some calculations suggesting a mass up to 200 times greater.

The star’s trajectory was likely altered by a celestial collision. Dr. Matthew Graham, the lead researcher from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), elaborated on the potential cause of the fatal orbit:

“The star may have collided with another large object that sent it into a long, stretched orbit, bringing it dangerously close to the black hole where escape became impossible.”

This fatal orbital perturbation caused the star to be subjected to extreme tidal forces as it approached the supermassive object. The differential gravitational pull across the star’s structure caused it to be vertically stretched and horizontally compressed, a catastrophic process vividly termed “spaghettification”. This elongation transformed the star into a stream of superheated plasma.

The fate of this stellar material was the formation of a glowing disk of remnants swirling rapidly around the black hole before the material was eventually consumed. It was this violent process of accretion and the subsequent frictional heating of the matter that resulted in the release of the record-breaking flare of light and energy. This observed energy burst provides empirical data to validate theoretical models of TDEs, which predict the tremendous energetic output when massive stars are disassembled by supermassive black holes.

Observation and Implications for Early Universe Study

The monumental event was successfully captured and analysed using a network of powerful astronomical instruments situated in various locations, including California, Arizona, and Hawaii. The ability of these telescopes to capture light from a source 11 billion light-years distant underscores the sophistication of modern observational astronomy. The observation of this hyper-luminous TDE from the early universe holds profound implications for understanding the physical conditions and the frequency of such extreme events in the past.

The study of this ancient light allows researchers to probe the accretion mechanisms and growth rates of supermassive black holes in the early universe, which are crucial for the development of modern cosmological models. The sheer energy involved suggests that such TDEs could have played a significant role in heating and ionising the early intergalactic medium, influencing subsequent structure formation. The detailed spectral analysis of the flare’s light will undoubtedly provide unprecedented information about the chemical composition and temperature profiles of the stellar remnants as they were consumed.

Conclusion

The detection of the brightest black hole flare in cosmic history represents a monumental achievement in observational astrophysics. The event, caused by the spaghettification of a massive star by a 300-million-solar-mass black hole, offers a rare and powerful demonstration of the most extreme gravitational forces at work. Not only does this observation validate complex theoretical models of tidal disruption events, but the immense distance to the event provides a unique time-capsule view, allowing scientists to study the violent dynamics of the universe’s earliest stages. The data gathered from this record-breaking phenomenon will continue to drive forward our understanding of the formation and evolution of supermassive black holes and the galaxies that host them.